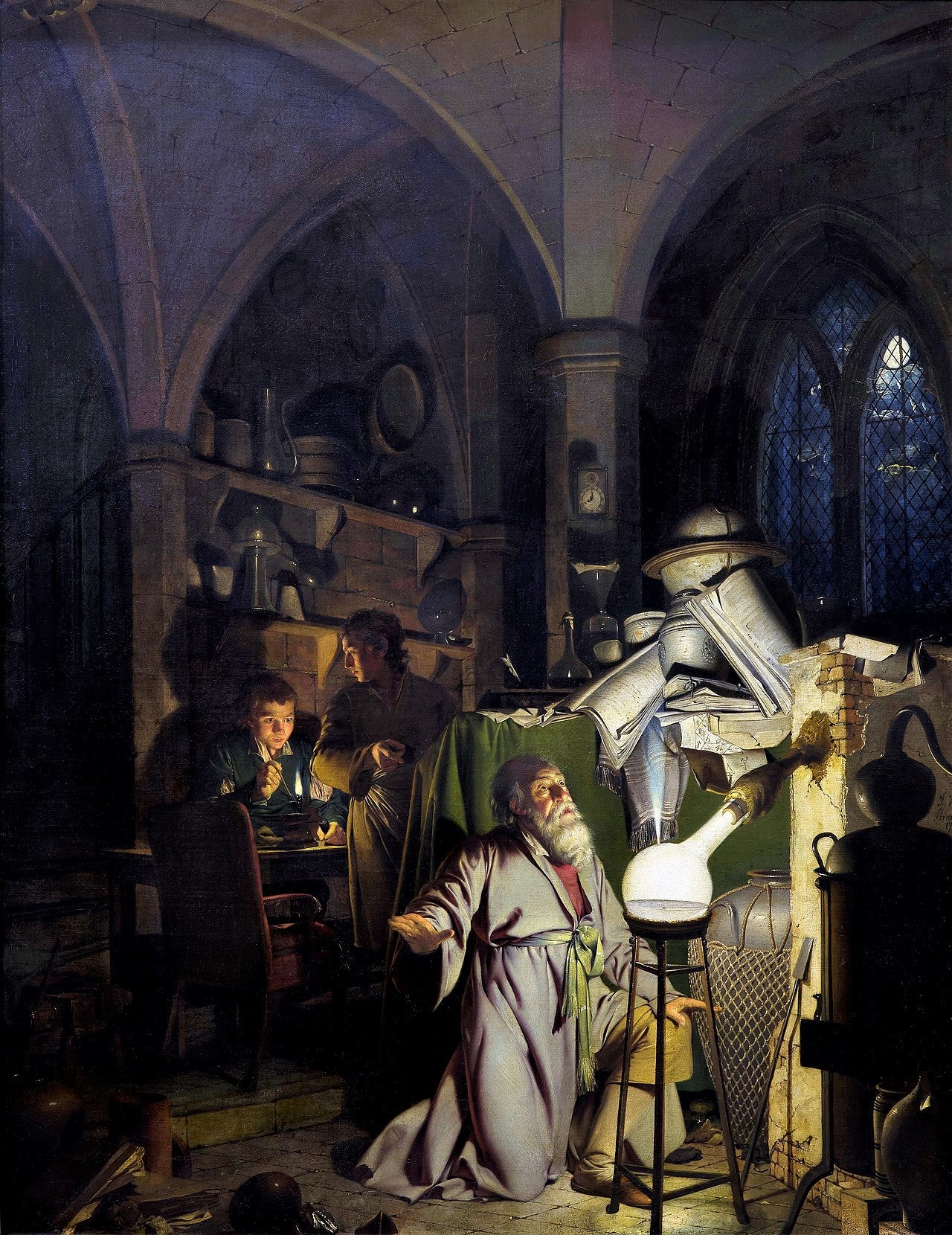

Science is an Art

And both require seeds of delusion.

Persistence is one of those traits that everybody recognizes is important but few actually understand.

There are two components of persistence:

The first, as characterized by Winston Churchill, is “the courage to continue.” This ability is crucial — facing failure after failure in pursuit of ultimate success without giving up along the way. This part of persistence is generally well-understood (though not often possessed) so I will not dwell.

The second is self-belief. This one is really misunderstood.

Self-belief is not simply agreeing with others who think you will succeed — it is disagreeing with those who think you will fail.

Self-belief requires disagreeableness. The more ambitious and revolutionary your work is, the more people will doubt you, and the more disagreeableness you’ll need to access.

Not only will people doubt you — they’ll have good reason to. After all, if success were obvious, why would anyone doubt you at all? Doubting you is often even the rational decision, supported by the analytical frameworks of the day.

Originality requires intuition defying reason; a seed of irrationality that will eventually be proven right, often by updating the very “rational” frameworks used to prove it. Persistence is driven by an irrational belief that you will succeed. There’s a reason why it’s also called “having faith in yourself” — it requires the same axiomatic, unerring belief.

I believe that this is the primary difference between the mindsets of science and engineering. Science is about furthering our understanding of the natural world, engineering is about exploiting scientific truths to solve practical problems.

A good way to understand this difference is by visualizing all of human knowledge as one big shape, or “convex hull” on a graph. Science aims to extend the boundaries of this shape, engineering aims to connect points within it.

With this analogy, we can see how the creative requirements of these fields differ. The engineer lives out a fruitful career merely by proof — his role is to leverage established formulae to solve tractable problems. He will never need to hold irrational beliefs, and in fact takes great pains to purge himself of any hints of such.

The scientist, in contrast, relies on such beliefs. Those seeds of delusion called intuition constitute the very basis of discovery. Henri Poincaré puts it succinctly:

"It is by logic we prove. It is by intuition we discover."

A perfect example of this duality is found in Albert Einstein and John Von Neumann. Don’t take it from me, but from Nobel laureate Eugene Wigner (edited for concision):

I have known a great many intelligent people in my life: Max Planck, Max von Laue, and Albert Einstein, among others. But none of them had a mind as quick and acute as Jancsi von Neumann. I have often remarked this in the presence of those men, and no one ever disputed me.

But Einstein's understanding was deeper than even Jancsi von Neumann's. His mind was both more penetrating and more original than von Neumann's. Einstein took an extraordinary pleasure in invention. Two of his greatest inventions are the Special and General Theories of Relativity; and for all of Jancsi's brilliance, he never produced anything so original.

There is no doubt that Von Neumann’s mind was singular and exceptional. But, as Wigner points out, despite Von Neumann being a divinely gifted engineer, the act of original creation favours the Scientist.

To tie this back to the idea of self-belief: nobody questioned the veracity of Von Neumann’s work — yes, he had detractors, but almost nobody thought his ideas were factually untrue.

Einstein, on the other hand, was proposing ideas so original that leading physicists of the day thought he was crazy — “Princeton is a madhouse and Einstein is completely cuckoo,” wrote Robert Oppenheimer. Einstein had to maintain an almost messianic self-belief, sustained over years, to shepherd his ideas to light.

This implies that the archetypical engineer need not exhibit self-belief. Doubtless, he needs to possess Churchill’s courage to continue. But in a world of perfectly behaving engineers (“the efficient-engineering hypothesis”, à la efficient-market hypothesis) any aberration from consensus is a mistake to be corrected. In reality, this hypothesis doesn’t quite hold, and people usually aren’t fixed into only one mindset (many engineers are even part-scientist). And don’t mistake this as being disdainful of engineers — they require their own forms of creativity, it’s just a distinct mode of thought as required by science.

This is part of why academia isn’t producing as much original thought as it once did. Universities are plagued by a paradox: extolling the fruits of revolution while casting out revolutionaries. A modern example is Katalin Karikó inventing mRNA vaccines. She was rewarded for this miraculous feat of science by being denied tenure and subsequently pushed out of the University of Pennsylvania. Only once her merit became undeniable was she awarded the Nobel prize. Karikó embodies Nicholas Klein’s quote: “first they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. And then they attack you and want to burn you. And then they build monuments to you.”

This recurring motif (seeds of delusion, breaching the convex hull of existing knowledge, fierce opposition, irrational self-belief, and eventual redemption) is present in all creative endeavours. And so, all creative endeavours are alike in this way — the mind of a scientist is more similar to that of a great artist than it is to an engineer.

Few scientists embrace the unity between science and art so literally as the father of neuroscience Santiago Ramón y Cajal whose early sketches of neurons are strikingly beautiful, shown below. His ideas were heretical at the time, causing renowned cell biologist Camillo Golgi to dismiss him for years, including in his Nobel acceptance speech — for a Nobel prize he was sharing with Cajal.

There’s something else to be said about the relationship between science and having faith in yourself. It lends itself to having faith more generally, and from my experience scientists tend to be more religious than their engineer counterparts. A scientist I respect deeply, who I worked with on deciphering mechanisms of gene expression, told me “God is speaking to me through DNA.” Joining him is Sir Francis Bacon: “a little philosophy inclines man’s mind to atheism; but depth in philosophy brings men’s minds about to religion” (a quote misattributed to Heisenberg, himself a practicing Lutheran).

Another activity belonging to the paradigm of creative discovery is founding a company. In addition to all of the above-listed attributes, entrepreneurship is unique because it also remains grounded in practicality and lived human experience. This enables you to actualize ideas not as mere abstractions but as agents of change towards aesthetic and moral values. This could be why Andy Warhol called business “the most fascinating kind of art.”

If Cajal is the perfect example of the artist-as-scientist, then Steve Jobs is the perfect example of the artist-as-founder — and not just for his love of design. Jobs’ most artistic aspect was his “reality-distortion field,” his ability to communicate and share his seeds of delusion with his team, enabling them to accomplish impossible tasks.

The idea of artist-as-founder goes well beyond companies. Nations are founded, with all of the hallmarks of creative acts (and then some). The Founding Fathers were, in effect, artists.

It goes even further than nations. The act of founding includes philosophies, cultures, even religions — but I think you get the idea by now.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Great Stagnation coincides with our embrace of rationalism and the subsequent rejection of religion/purge of the mystical. How many Karikós have been “straightened out” of non-rational thoughts long before even having the luxury of being expelled from the academy?

In conclusion, all creative endeavours, whether science, entrepreneurship, nation-founding, or art itself, share a common pattern of thoughts. Chief among them is requirement of initial delusion that needs to be nurtured with irrational self-belief until ultimately being proven right. To master creativity is to harness delusion.

And of course, not every delusion results in revolution.

But every revolution begins in delusion.

This essay replaces an earlier piece that felt incomplete called Persistence Prevails. For posterity, it’s available here. Thanks to Lola Wajskop for inspiring some of the ideas in this essay.

The theme of encouraging original creation is also explored in The Feedback Tradeoff, which advocates isolation during ideation while this essay encourages disagreeableness and relentless self-belief. Both are true.

Stubbornness is underrated. You'll enjoy this essay: https://www.juandavidcampolargo.com/blog/stubborn

Reminded me of the story of the king.