Henry Ford said:

"If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses."

Y Combinator disagrees:

“Talk to your users.”

Are these statements at odds?

This framing implies a binary — you’re either a people-asker or a solo-thinker. The truth is more nuanced.

A tradeoff occurs every time you get feedback. You become slightly more mainstream, slightly more aligned with the zeitgeist. You become marginally more of an exploiter than an explorer, standing on the shoulders of the giants who conceived the paradigm you’re striving to build upon. This is very effective when you want to align your work with others. But you also stray from the path you were exploring.

In many cases, this is a good thing. In rare cases, it’s an utter tragedy.

By trading your current path for a more popular one, you inch closer to the local maximum but potentially further from the global maximum. Again, most people, at most times, should not be exploring (a topic for another day). But when you are, let your weird thoughts be weird and encourage your natural exploration by eschewing the feedback of others.

It’s not a coincidence that some of our most daring thinkers and revolutionary scientists had their groundbreaking ideas when insulated from feedback.

Newton discovered calculus, optics, and gravity. Not during his time at Cambridge, but while quarantined on a farm from the Great Plague of London. Already having been mentored enough to learn notation and methods, his ideas were allowed to flourish unmolested.

Einstein had his own annus mirabilis, discovering the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, the special theory of relativity, and the mass-energy equivalence. All of this was in 1905 while he worked as a patent clerk — not as a graduate student. Einstein conceived of his most significant ideas at the point of his life when he received the least feedback.

To be clear, receiving guided education is still very helpful, and both Newton and Einstein completed advanced schooling. And even the craziest thinkers need some feedback, at the very least to make their ideas actually accessible to everyone else. A great example of this is the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan.

A poor genius from India, he had no choice but to teach himself. Scribbling in his notebook, extrapolating from the few textbooks he got his hands on, Ramanujan created absolutely gorgeous bits of math.

Due to his isolation, he worked on fields less known among other mathematicians of his day. He solved previously unsolvable problems by inventing entirely new methods — because he was never taught the existing methods! Things are only impossible if you believe them to be, and nobody was around to warn Ramanujan to lose hope.

However, he waited a little too long to solicit some feedback, especially on notation and proofs. Not by choice, mind you:

"he tried to interest the leading professional mathematicians in his work, but failed for the most part. What he had to show them was too novel, too unfamiliar, and additionally presented in unusual ways; they could not be bothered."

Thankfully, G. H. Hardy took a chance on him, brought him to Cambridge, taught him to formalize his work, and provided the amount of feedback required to allow us to appreciate his wonderful genius.

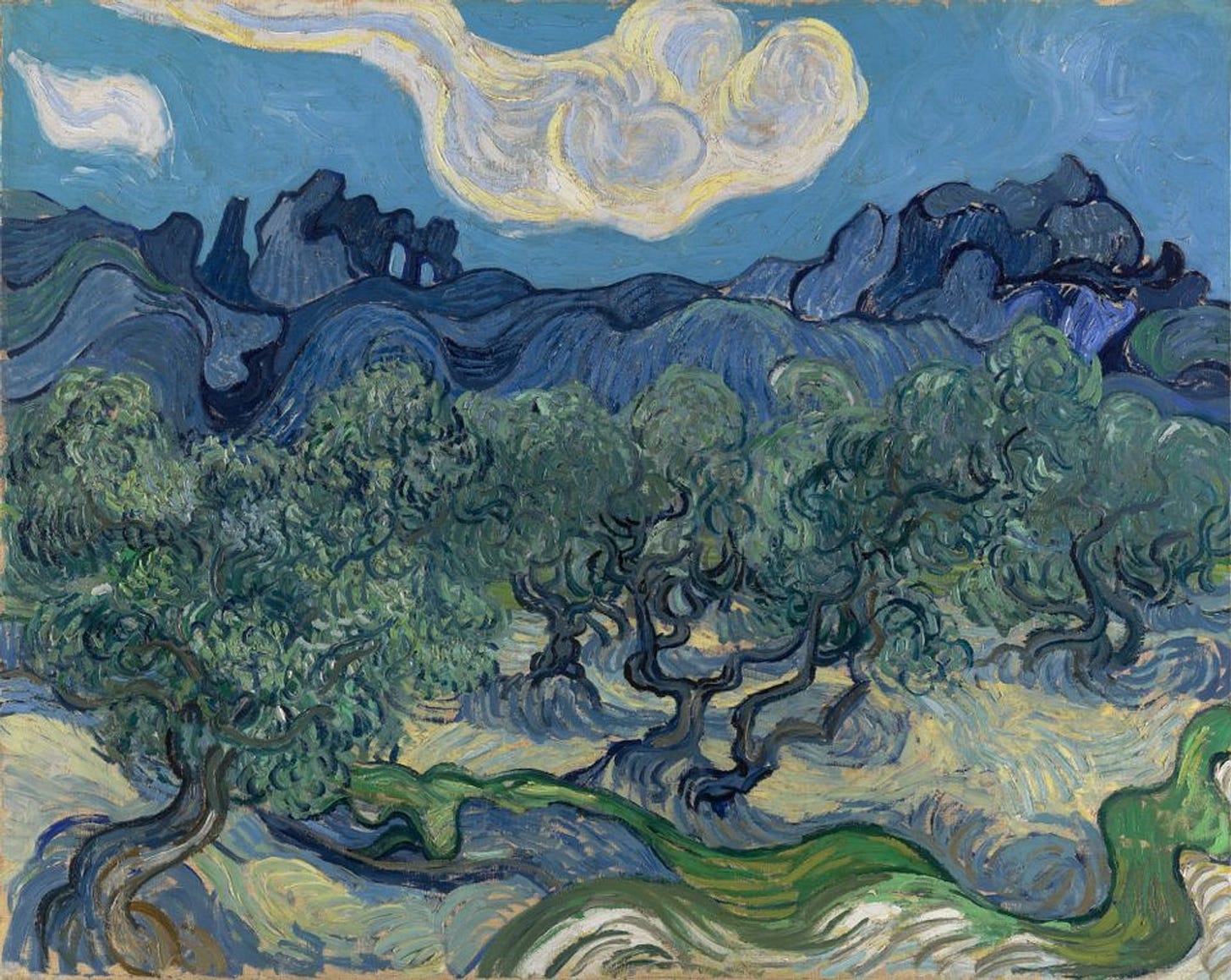

I’ve focused mostly on science and math, but this goes for anything. Take Vincent Van Gogh, one of the greatest painters to ever live. He was mostly self-taught, but for the few months that he was in art school, he was criticized for his unique style. Here’s The Art Newspaper on Van Gogh’s time without feedback:

Cut off from the latest art in Paris, Van Gogh followed his own path. Within the asylum’s walls he developed his art in a highly personal and idiosyncratic way, almost uninfluenced by his peers or by market considerations. This left him free to take bold artistic decisions, creating the Van Gogh that we now love.

Feedback exists in many forms. So far, I’ve considered feedback as explicit, honest, and from a knowledgeable person invested in your success. This is not always the case, and feedback is often misguided or even malicious. There’s the classic trope that your mother will only give positive feedback, while your mother-in-law will only give negative feedback. The schools in a propagandistic society will be full of misleading feedback. Yes-men definitionally give the feedback that will help their careers. These brands of feedback are never helpful for idea-honing, and should be treated differently altogether than the ideal-case feedback I’ve been describing so far.

There is also implicit feedback whenever you publish something publicly — if a scientist publishes his findings as he makes them, his more mainstream ideas will earn more attention than his wacky ones, and he will adjust accordingly. It’s no surprise that breakthroughs are so often produced by those unfettered by well-received ideas.

Avoiding feedback also doesn’t mean complete social isolation. A small research lab or a mission-driven startup can approximate a single mind and explore freely. But it does mean taking your own ideas seriously enough to see them through, even if others disagree. Even self-doubt as a form of feedback needs to be carefully regulated.

I have had the pleasure of meeting a truly exceptional inventor who takes this concept to the extreme. He doesn’t even read books because he doesn’t want to influence his subconscious. I don’t necessarily advocate this level of creative independence, but he has a genuinely enviable track record, so maybe he’s onto something.

No doubt some of the worst ideas also occur without feedback. Even within an individual thinker, the people who invent transformational paradigms often invent some pretty bad ones, too (see the Nobel Prize effect). But that’s the whole point of exploration — it’s a high-variance, right-skewed activity that usually accomplishes nothing, except for when it completely changes the game. Feedback raises the median outcome of exploration at the cost of reducing variance, making it marginally more like exploitation.

Be aware of this Feedback Tradeoff and how it interacts with your goals:

If your goal is to create a popular version of a well-established thing, like a pizza parlour, seek plenty of feedback.

If your goal is to create something somewhat novel that still requires stakeholder buy-in, like a tech company, avoid feedback during exploration phases and seek feedback during exploitation phases. Going back to the two opening quotes, YC is suggesting you talk to users to iterate solutions towards the local maximum (exploitation phase) while Ford was suggesting that you don’t solicit feedback when conceiving potential solutions (exploration phase).

And if your goal is to unearth entirely new planes of understanding, avoid feedback like it’s the Great Plague of London.

Just read this from a share on X. Excellent stuff. A balanced understanding of feedback is key.

Super helpful points, thank you!

Are you familiar with MrBeast? Michelle Jia (of Sundogg substack) and I recently published a documentary on his life and influence, and one of the wildest things was how he lived his entire life guided ONLY by explicit, numeric feedback. He makes YC look like hermits!